About the IWML report

The aim of “Irgendwas mit Logistik” is to make the subject area accessible through the podcast of the same name and to present it in such a way that it can be consumed anytime, anywhere – on the way to work, on a rainy Sunday on the couch, or in the bathtub. The team also offers its own videos on YouTube. In the regularly published IWML reports in PDF format, experts provide in-depth insights into projects and market developments, packaged in an appealing design.

The article presented here first appeared in the fifth report “Warehouse Management Systems – (More than) Eight Tentacles for a Hallelujah” (German language)

About GRASS

As a development partner and system provider to the furniture industry, GRASS has been creating products and services that inspire customers for more than 70 years. GRASS slide and drawer, hinge and flap systems are brand-name products that are integrated into furniture by renowned manufacturers. With sales of 467 million in the 2021 fiscal year, over 1,800 employees at 19 locations, and more than 200 sales partners in 60 countries, GRASS is one of the world’s leading specialists in opening systems.

Here be dragons - or how white spots on the automation map become solutions

In the dim and distant past, when maps and the internet were still printed on parchment terminals, it was common practice to decorate unexplored territory with mythical creatures. “Here be dragons” is the original Latin phrase “Hic sunt dracones,” which served as an ancient warning sign on land and at sea. Today, it still exists in the English-speaking world as a pop culture reference and as a tongue-in-cheek label for unknown or unclear codes in a software project. In the following report, Thorben Rieck and Manuel Bonner discuss the joint project between TUP and GRASS and the discovery of the opportunities and limitations of automation.

Setting out for the new world - The concept phase for the central warehouse

In 2014, the successful manufacturer of furniture movement systems, headquartered in Vorarlberg, Austria, embarked on a journey into the unknown, as its decentralized, manual warehouse structure had reached its limits: Driven by growth, the locations maintained several finished goods warehouses in addition to the production warehouses, some of which were operated by third-party providers. This resulted in a multitude of standards and intralogistics processes. An interim solution was needed to allow quality and service levels to grow with the customers. In the concept phase, the GRASS project team therefore sketched out an initial picture of the new world: Transport between the plants was to be automated, as were various manual activities. A paperless system was envisaged that would support employees in both picking and order picking using software. The focus was also on linking processes that had previously had no direct connection to each other, with the aim of being able to deploy operational staff more flexibly in the future.

The construction of a new logistics center in Hohenems as a distribution center for the production plants in Austria and Germany was intended to cover the planned growth until 2025. By that time, the company expected logistics costs to increase by 45 percent due to a doubling of the product range in stock. As part of the interim solution, a kind of pre-central warehouse was rented in a listed building in Feldkirch to take the first step in consolidating the distributed locations and different processes.

GRASS employee Manuel Bonner recalls: “It was a huge, old hall with 10,000 pallet spaces. The square footage and number of employees were correspondingly high, as we could only work with shelving systems there. Visually, it was a great hall, half of which is listed as a historic building. Everything was still brick-built and, at that time, equipped with huge automatic looms. Beneath it, there were veritable catacombs to discover, which presumably served as storage space.” The location was intended to bridge the transition phase to Hohenems from 2018 to 2020.

Particularities from the intralogistics perspective

GRASS customers are renowned furniture brands with high-quality products. Accordingly, high standards and very precise specifications, from the appearance of the goods to their arrangement on the pallet, must be met. In Feldkirch, these instructions and specifications were still documented in paper form in numerous folders. As the company’s success story continued, the two production plants in the Austrian Vorarlberg communities of Götzis and Höchst developed in two very different directions: Höchst primarily served industrial customers. The pallets were therefore loaded with large cartons that could hold between 150 and 300 products. Götzis, on the other hand, handled a mixture of industrial and small quantities and individual items. This created the challenge of keeping together a pallet that could consist of hundreds of individual items.

The old world - Predominantly manual intralogistics

In order to maintain high quality and throughput in this predominantly manual intralogistics environment, employees specialized in individual areas and customers. However, the long training periods required for this had an impact on flexibility on site. The tools used to process order progress and allocation were primarily Excel, paper, and the telephone. An order center already centralized at the Feldkirch site compiled the picking orders and handed them over to the pickers. The numbers of specific instructions were added to the handouts themselves. Experienced staff knew these by heart in most cases and could implement them directly. However, inexperienced employees, especially during the training phase, occasionally had to return to their workstations to recall certain codes, such as “45” meaning to place the left and right parts together on a pallet.

In Feldkirch, the processes had already been optimized as far as possible for a central location by starting with a comprehensive analysis. After all, the core challenge is not the incoming or outgoing goods, but rather, especially at GRASS, the processes that take place in between them in the warehouse.

Complex solutions were not always necessary to manage the complexity arising from the wide range of requirements: the GRASS team approached customers in open discussions, showed them which requirements had already been implemented, and offered these accordingly in order to ensure standardization in this area as well. The lack of real-time tracking was particularly noticeable when the daily load was exceeded, due to the combination of a still-growing digital infrastructure and cooperation with third-party providers. This required a great deal of communication between dispatch control and logistics specialists: What could wait and what had to leave the warehouse on the same day? Even with advances in digitalization, simply calling the carrier and telling them to pick up 200 pallets today is unlikely to be successful in most cases.

In the second step, the existing processes were brought together in intensive discussions and workshops. This was because the knowledge, some of which was not written down and had grown organically, was stored in the minds of the employees and provided a valuable insight into the present and the future. What later proved its worth in the conception phase was the inclusion of those who had seemingly little contact with the issues at hand. Everyone was given the opportunity to contribute to the questions about the quality and improvement potential of the processes. This increased acceptance of the project and paved the way for the establishment of a lively and open feedback culture.

In the course of the analysis, the image of the new world that Hohenems was working towards also took shape: instruction folders and coordination phone calls were to be a thing of the past. In addition to these paperless processes, the goal was for a person to be able to work independently on the system within half an hour without needing a huge amount of background information. At the same time, the system had to offer users a high degree of process reliability, meaning that an incorrect entry or selection should never bring the entire system to a standstill. The three pillars of the new world can be summarized as follows:

- Paperless: The order slips were to be replaced by mobile devices that would provide employees at stationary workstations and on round trips with real-time information.

- Safe: The plan was to make work more ergonomic and safer through automation and the use of lifting aids. The system was to provide suggestions for courses of action to ensure that even inexperienced workers could work with a high degree of process reliability.

- Simple: The processes were broken down into individual steps with clear work instructions. This means that standard scenarios such as under-stocking or missing inventory could be reported directly to the WMS. As a result, the information no longer had to be communicated between employees, saving time and effort.

How intralogistics processes were evaluated and transformed by TUP and GRASS

The crucial point in all automation projects is whether the processes can be broken down to such an extent that they run automatically in most cases and all the finer details or refining steps can be cleverly decoupled from these processes and then recoupled again. This requires very precisely described and, above all, prioritized processes. “In our joint discussions, the team used the catchy categories of core process, peripheral process, and ‘better living’ as a nod to the range of products,” recalls Manuel Bonner.

The diverse requirements of small shipments and industrial customers had to be reconciled. In the end, eight or nine requirements remained, on the basis of which the core process and the necessary software could be designed. To this end, complex customer-specific requirements were partially decoupled from the picking process and outsourced to a separate area with its own department. Simpler issues, such as placing left and right parts of a system on the same pallet or smoothing heights, were integrated directly into the core process.

Another major advantage was the team set up within GRASS: Manuel Bonner brought four years of experience in operational logistics to the table. This meant he not only had valuable insight into the processes, but also good contacts in the departments and the trust of the shift supervisors.

As project manager, Jürgen Moritsch initiated the tender process and reliably guided the project team through critical issues, thanks to his experience in the company’s logistics world, which he has been building since 2007.

Rene Malojer earned his spurs as a working student in strategic logistics, quickly took on personnel responsibility, and specialized in areas such as order-to-cash processes and order intake.Both the GRASS and TUP teams quickly realized that not everything planned on paper was realistic—especially where people and physics came into play. But by focusing on the core process and the mantra of the intralogistics software experts, “Software follows function,” the goal of a pragmatic solution, without getting too caught up in trends, was always in sight.

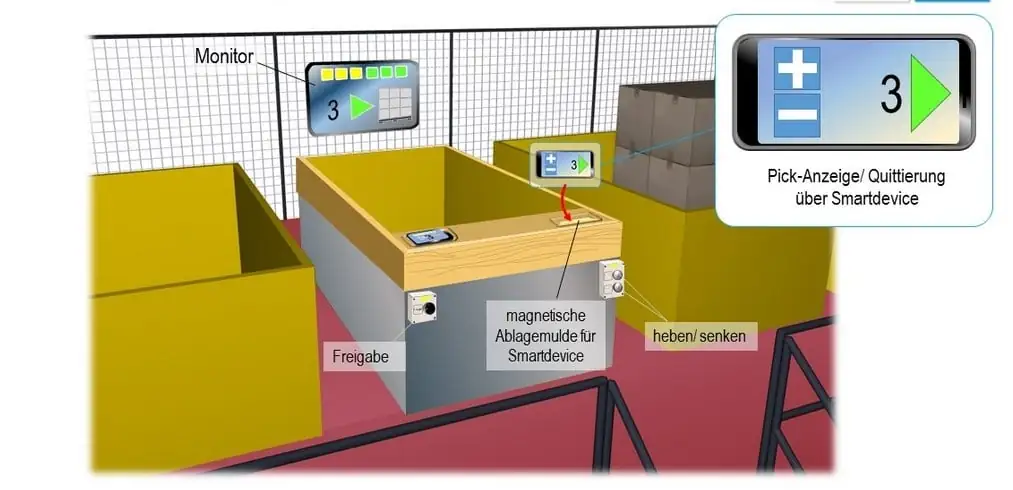

The use of a palletizing robot was quickly rejected and the hybrid picking system was developed instead. Here, the classic setup of the pick-by-light principle is replaced by detailed dialogs on mobile devices.

The crucial point in all automation projects is whether the processes can be broken down to such an extent that they run automatically in most cases and all the finer details or refining steps can be cleverly decoupled from these processes and then recoupled again.

– Thorben Rieck

In the pick-by-light approach, pickers receive visual instructions on the number of units to be picked in relation to the item via pick indicators at the staging areas. The pick indicators are usually located directly above or below the staging area and also have correction options and a button for confirming the removal. There are also area displays for multiple locations. (See “Put to Light” or “Pick to Light” – Source: logipedia / Fraunhofer IML)

This allows new use cases to be mapped, for example, in the GRASS context, the sorting of pallets. The workers are the central authority in the workflow of the hybrid picking form and are supported in the best possible way. The system provides them with the pallets in sequence via the conveyor system, thus minimizing distances and throughput times. In addition, the pallets are delivered vertically at an ergonomically correct picking height. Experienced employees can move freely within the scope of their tasks thanks to the responsiveness of the workstations. New staff do not need time-consuming training, but are guided step by step through the process by the system.

A palletizing robot, on the other hand, would have required excellent master data as well as additional identification features on the package itself and would have had to meet the two very different requirements of industrial and small orders. This, in turn, would have cost time and resources and resulted in too many uncertainties for the core process. This focus on the core process also led to some replanning, in which bypasses were created and overall resilience was increased to prevent possible downtimes in the event of an incorrectly routed pallet.

A key criterion for going live was the fundamental trust and, above all, the collaboration on equal terms between GRASS, TUP, and other companies involved. Everything could be discussed openly and the most pragmatic approach was always sought. This was also necessary because the coronavirus pandemic coincided exactly with the planned commissioning date in July 2020. Although overcapacity had been planned for, with many sectors of the economy on short-time hours and the resulting supply chain bottlenecks, only core personnel continued to work.

Embarking on a new journey - How the greenfield project impacted business processes

Before commissioning, the possibilities for automation and digitization were limited.

Then, on June 19, 2020, everything suddenly changed. The system was linked to the TUP software, bundled under the acronym GRALIS (Grass Logistics Information System), and put into operation. This also marked the start of the relocation from the existing sites, with a focus on moving from Feldkirch to Hohenems as quickly as possible.

In Vorarlberg, the company had brought in two additional logistics service providers with 9,000 and 2,000 pallet spaces to support the pre-central warehouse in Feldkirch with 15,000 spaces. The approximately 20,000 pallets were to be sold off and newly produced goods were to be transferred to the new central warehouse. To this end, the personnel, order situation, and available transport capacity were mapped out daily on Excel and successfully managed. There are good reasons why the good old Microsoft tool is still going strong.

Software is often a no-man’s land for someone working in logistics, which is why experts are needed. That’s why we placed great importance on receiving the right support from the software providers.

– Jürgen Moritsch, strategic logistics expert at the GRASS Group

The new automation technology

GRALIS operates independently in the goods receiving area of the new central warehouse in Hohenems: trucks dock and the fully automated system unloads pallets within three minutes without the involvement of personnel. Fifteen minutes later, the goods are stored and available for orders. The counterpart at the end of storage is a sequential goods issue. Using two separate double-deep shipping buffers, tours are pre-sequenced: goods are removed from storage within an order from heavy to light in order to optimize truck loading. Each object transported in the system manages its own orders: from labeling and inspection to compartment search. The set of rules for this type of order is also connected to the pallet conveyor system via an interface, which ensures that actions are processed in an orderly manner. For example, parts lists can be ideally served for the picking process.

Each pallet picking station is equipped with two control screens and two permanently assigned MDTs in accordance with the hybrid picking principle. The devices are linked to each other per station and across the entire work area and communicate as a unit with the conveyor system. The screens provide users with visual guidance and a real-time multimedia overview with information on the current pick and the work queue. Pickers can interact directly with the GRALIS WMS via MDT dialogs. Additional tasks, such as customer-specific requests, can thus be implemented during the picking process.

We simplified the complexity wherever possible. Communication between the central team members, external partners, and those responsible for operations in Hohenems was crucial.

Our entire planning was based on Excel, where we mapped out the entire warehouse. We compared this every day and thus knew where things were not going well or where we were even ahead of schedule.

– Rene Malojer, Head of the Central Warehouse in Hohenems

Each pallet picking station is equipped with two display screens and two permanently assigned MDTs in accordance with the hybrid picking principle. The devices are linked to each other per station and across the entire work area and communicate as a unit with the conveyor system.

MDT is an abbreviation for “mobile data terminal” or “machine data terminal.” In this case, the abbreviation is colloquially used in reference to the device used for data entry.

The screens guide users visually and provide a multimedia overview in real time with information on the current pick and the work queue. Pickers can interact directly with the GRALIS WMS via MDE dialogs. Additional tasks, such as customer-specific requests, can thus be implemented during the picking process.

24 hours before delivery, the departure time, route, and loading container are created. At this point, it is known when the truck is scheduled to depart, which shipments will be loaded onto the truck, and which customers have placed orders (it is also possible for a single company to place multiple orders). No later than two hours before the departure time, the pallets are automatically transferred from the high-bay warehouse to two shipping buffers with a capacity of approximately 460 pallets. Here, the day’s shipping volume is correctly sequenced and pre-buffered per tour.

The first steps into the unknown - The launch of the Greenfield project

In the three months following July 2020, the new and old central warehouses operated in parallel until the inventory could be completely transferred or sold off. Day one in Hohenems was a big bang for all employees, both technologically and in terms of working methods, because suddenly everyone was in the new world. “There was a lot of tension, especially in the control room. We weren’t used to placing so much trust in a system when we had previously had full control with slips of paper, the telephone, and Excel,” says Manuel Bonner, summarizing the launch.

In order to establish and nurture this trust in a timely manner, the project team focused on transparency, participation, and rapid integration of feedback—but also on rigorous proof of concept in cases of greater concern. The fear of ruining the entire system with a false confirmation was alleviated, for example, by saying – in the presence of the project team, of course – “Just press ‘OK’ and see what happens.” So-called super key users were defined for the training courses, who were to pass on their knowledge to the employees who were gradually joining the company. This prevented twenty or more people from being rushed through a lecture-style session, only to forget half of it afterwards. Instead, GRASS established a train-the-trainer model in which all participants interacted directly with the system via computer or MDT from the outset. With this approach, a small group of people are first trained in great detail so that they can then pass on their knowledge to others. Even special situations, such as repeated requests for paper-based work instructions for the new workstations, were solved with Vorarlberg nonchalance by sending the person to the hybrid picking station with the announcement, “Go on stage for fifteen minutes and tell me if you need work instructions.” The result after 20 minutes: “OK, we don’t need them.”

At the same time, the project team was also very open about the fact that after going live, there is always still work to be done. “What we planned at the round table wasn’t always perfect. No matter how well you analyze the process, no matter how intensively you talk to stakeholders and employees beforehand, as soon as you arrive in the real world, something will always be missing or go wrong,” Thorben Rieck sums it up. Often, it was small things that were automatically compensated for by people in manual and paper-based processes. In Feldkirch, for example, it was not particularly important how high a source pallet was, because the human factor automatically compensated for this. With an automatic high-bay warehouse, on the other hand, it is very important to know exactly whether the pallet is moving into or against the rack. It quickly became apparent that a long, detailed look at the master data was necessary for the automatic height calculation to work smoothly.

Thanks to the iterative approach, which was supported by all those involved, development never stood still. This also led to a change in culture at GRASS: everyone involved in the process was a stakeholder whose feedback was heard, processed, and integrated. And this yielded tangible results immediately after commissioning: While goods receipt for commissioning was still handled via a PC workstation, in a later iteration it had already migrated to an MDT. The process remained the same, only the input medium became more user-friendly.

The challenges of transitioning from a paper-based to a web-based world

Large red buttons have one decisive advantage: their spatial arrangement and wiring make it very difficult to press them simultaneously. In the digital world, it was necessary to clarify who is right when “left” and “right” are pressed simultaneously at a station via the MDTs. To do this, mechanisms and approvals had to be developed to determine which input is decisive in the event of input conflicts. If everything can talk to each other, everything must also understand each other. For sources, targets, and the working groups in between, it was essential to communicate with each other in real time without creating blockages or misinformation. The obvious solution was to shift as much control as possible to the digital realm, which meant not utilizing the potential of the workers. Manuel Bonner and Thorben Rieck sum it up: “Originally, the idea was this: the pallet is planned in advance, the layering is calculated, and in the end, everything is wonderful. Of course, this assumes that the master data is clean, that everything is calculated correctly, and that the pallet is intact. These are all things you don’t know in advance, and if one board on the pallet is broken, you have a process that comes to a standstill.”

The perfect middle ground for us is that employees have very clear guidelines on how to sort items, but at the end of the day, they can still decide for themselves what to process and ship first. In the digital world, we know the routes and how heavy the boxes are, but when it comes to the physics of the real world, it’s the workers who know best.

– Manuel Bonner

The system provides a suggestion, but ultimately it is the employees who decide whether and when an order is complete. After all, humans are still the best cybernetic system we know. GRASS exploits this potential with its hybrid picking system, which provides ergonomic service and lots of helpful context, but still leaves the important decisions to humans. Human intelligence makes better decisions, especially in borderline cases or when pallets are damaged.

Beyond the horizon? Only more horizon - The next steps for the future

Further adjustments were made immediately after going live. The logic of some processes that previously ran manually was adjusted. They were moved to a location with more automation and better lifting aids in order to maintain high performance and reduce strain on employees. The target of 1,300 pallets loaded per day with a delivery service level of 99 percent was already achieved during the ramp-up phase.

The fact that we were able to deliver and invoice from day one of commissioning speaks volumes about the quality of support before and after go-live.

– Helmut Kainrad, CFO of the GRASS Group

Thanks to further adjustments and ongoing employee training, the planned peak volume was even exceeded. There is also talk of adding a few more robots so that heavy picking tasks no longer have to be performed by humans. The lessons learned and the solutions developed jointly will also be applied in the future in production plants that are still operating with different software systems.