There’s always something going on with the agile approach. However, this article is not about praising the next three-word combination as a panacea. Instead, it’s about solutions, complexity, and the seven Rs of logistics, viewed through a lens that is not so new after all.

An overview of Minimum Viable Change approach

Minimum Viable Change (MVC) refers to the smallest possible but meaningful intervention in existing processes or systems in order to achieve measurable progress toward a defined goal. It is not about the principle of the “lowest common denominator,” but rather about the targeted reduction to what is necessary. Unlike Minimum Viable Product (MVP), which describes a functional prototype with a minimal feature set for market testing, MVC focuses on the management of change processes themselves. MVC asks: “What do we really need to change to achieve improvement?” – MVP asks: “What is the minimum we need to deliver to make a product usable?” This makes MVC particularly relevant in complex, mature system landscapes such as intralogistics.

Context is king

The seven Rs of logistics are: delivering the right product to the right customer in the right quantity, in the right condition, to the right place, at the right time, at the right cost. They are the key metrics for success in logistics. Minimum Viable Change is a compass for making the path to success as transparent, efficient, and secure as possible. This approach broadens the perspectives of the individual business domains involved to address the simultaneously very simple and very complicated question: “How much needs to be changed in order to achieve the desired goal?”

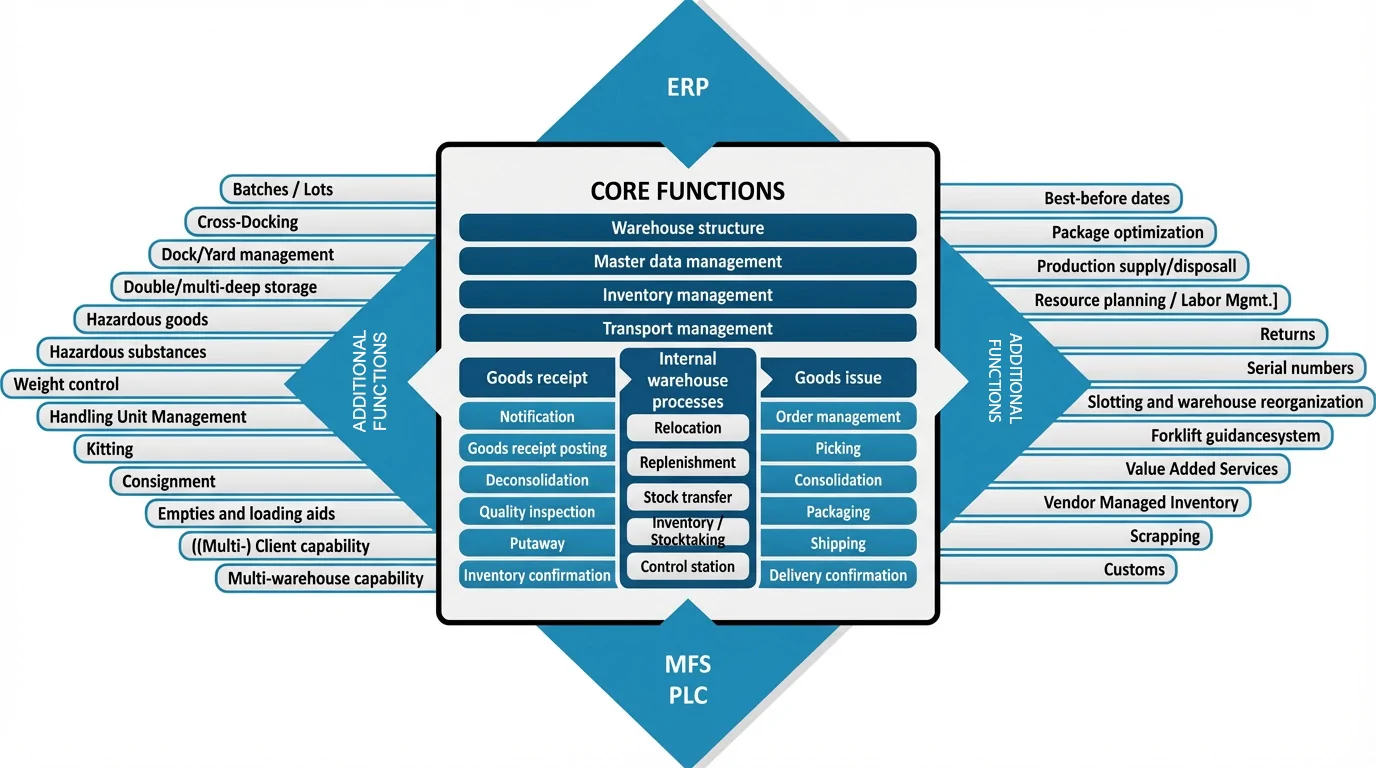

In intralogistics in particular, there are many paths from goods receipt to goods issue, and many processes are involved in the actual movement of inventory. The complexity and temptation to design a one-size-fits-all solution are correspondingly high.

If the MVC principle is followed, it already acts as a corrective measure here. The central question breaks down the barrier created by specifications and requirements, as well as by the customer and client constellation. The answer to this question can only be found through collaboration—first at the operational and ultimately at the strategic level. After all, the goal is not to find hardware and software solutions that look fantastic on paper but then require processes to be bent out of shape in order to implement them. Rather, the goal is to provide as much support as possible—but only as much as necessary—to the process. To this end, it is essential to work with all parties involved to jointly determine the current and target states: Software experts should ideally examine the processes from goods receipt to goods issue on site, while logistics specialists should familiarize themselves with the available digital tools. This allows the “why” behind each process step to be illuminated in such a way that a common path into the future can be planned. The initial planning then takes place on collaborative platforms. With a focus on functional clarity, chains are established – these give rise to work packages that are tested and operationally validated as quickly as possible or iterated using the insights gained. This fundamental approach runs through all phases of a retrofit or greenfield project.

The specifics of the individual project steps from an MVC perspective

The planning phase

It can be summarized under the motto “understanding instead of guessing” – ideally as an obligation for all project participants. This is because every project has its own unique characteristics, both within individual domains and across them. This initial phase is critical for all subsequent phases, as it is during this phase that a shared vision and, above all, a common language are developed, which will later form the basis for implementation. Collaborative project management and documentation tools are essential in this step to make all participants co-creators.

If the principle of minimum viable change is followed, this phase proceeds differently than in classic requirement and specification constellations. The focus is not on functions, but on application scenarios. This keeps the focus on the actual process. This type of planning is the basis for high speed and decision-making confidence later on – where, in a classic approach, the first misjudgments collide with the harsh operational reality.

The architecture phase

It combines functions with a supporting framework and must also be structured in such a way that granular changes are possible. This means that, ideally, the software side makes concessions to logistics and chooses its technical language as the basis for development, so that logistics specialists can make quick and transparent decisions about development steps. The logistics side must move toward agile methods, which are common on the development side:

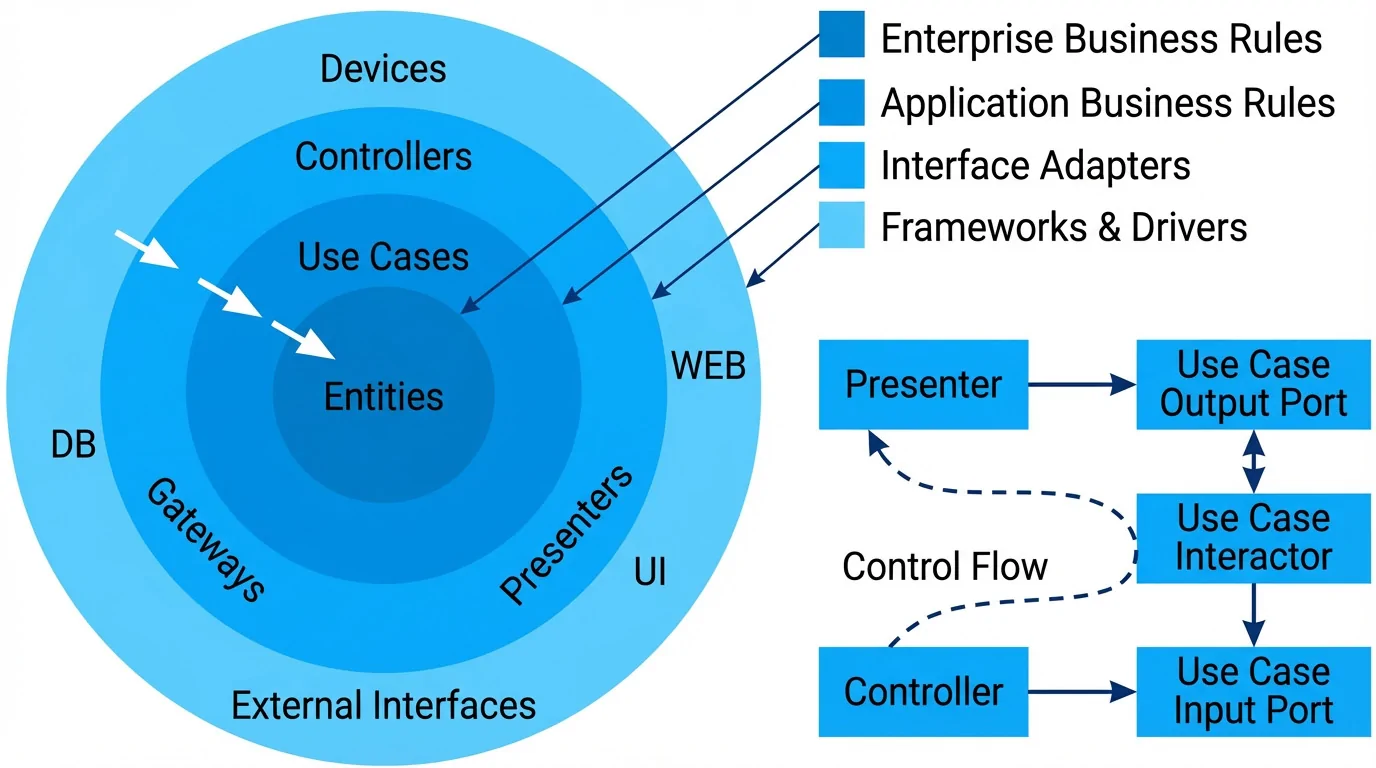

- Clean Architecture: The company’s use cases and business rules form the core around which functions, databases, and user interfaces are arranged. What is special about this is that dependencies may only exist from the outside in. One use case, for example, is communication with a service provider, which must be carried out according to specific business rules. In clean architecture, this can be done by email, phone, or chat, as the channels are not permanently linked to the business rules and therefore do not necessarily require a specific infrastructure.

- Test-driven design: Before software development begins, tests for the respective components are already defined. This ensures that the code is constantly confronted with real-world requirements.

- Clean domain boundaries: Especially in monolithic standard solutions, processes from different domains often get mixed up: Suddenly, accounting tasks end up in logistics processes — and warehouse employees search through miles of Excel lists for the right transaction numbers to finalize orders.

Infrastructure development

This phase must be able to map the planning and architecture phase: If implementation is to be small-scale, fast, and extensive, it must happen as smoothly as possible. In this context, “cloud” does not necessarily mean third-party data centers, but rather that computing power is viewed as a resource—like electricity or water. Physically, it consists of many inexpensive, highly networked hardware units in clusters. Redundancy is created at the software level because almost every process—from provisioning to monitoring to failover—is automated. Mature open-source systems such as Kubernetes now allow infrastructure to be controlled via code. This makes scaling plannable and verifiable, while operations teams can focus on process and quality improvements instead of manual infrastructure work. Automated provisioning is the basis for reproducible quality and scalability.

Implementation

Here, all parts mesh together to enable iterative, rapid development of tested and functional systems that create operational added value as early as possible. Because the communication channels and, above all, the technical language of the project have already been established in the previous phases, the project becomes a learning organism. To achieve this, the cooperating organizations and tools must be adapted accordingly. This is particularly evident in the integration of the warehouse management system (WMS): it moves between different worlds. Overlaying enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems control orders and bookings, while subsystems below it define machines, conveyor technology, and human-machine interfaces.

At the heart of the WMS are its core functions:

- Inventory management

- Order control

- Replenishment

- Order picking

In practice, the boundaries are individual and often fluid. Should the ERP take over the detailed planning or the WMS? Will the material flow computer (MFC) be encapsulated or directly integrated? These questions are best answered and checked for feasibility by the MVC principle using the know-how gained in the previous phases, the established workflows, as well as the equal-footed relationships between the project teams. In order for the warehouse management system to become the heart of the intralogistics organism – and ensure rhythm, supply, and synchronization – it must be individually embedded into the whole. While this sounds fantastic, it also means being willing to abandon plans and infrastructure if they no longer correspond to the principle of the smallest meaningful change.

Post-Launch

The process continues beyond initial implementation: companies and their logistics operations grow and change. The advantages of the MVC concept become apparent in long-term operation: if the teams on both sides remain in place, necessary changes can be made quickly and efficiently—and at significantly lower cost compared to big bang approaches. The ability to change continuously is the best way to respond to increasingly complex market situations without creating more complexity internally through major change processes.

Conclusion

The prerequisite for sustainable success is the ability to adapt to one’s environment. This requires knowledge, a willingness to take responsibility, and trust—as a basis for viewing and changing things without ideological or technical baggage. Minimum viable change is the guide for repeatedly going through change in line with one’s own business processes—by intervening only as much as necessary and as little as possible.